alyaza [they/she]

internet gryphon. admin of Beehaw, mostly publicly interacting with people. nonbinary. they/she

- 1.55K Posts

- 984 Comments

18·4 days ago

18·4 days agoLife expectancy in the country has now risen above the United States, to 78 years, from just 36 years at the time of the Communist revolution in 1949.

But China’s retirement age remains one of the lowest in the world - at 60 for men, 55 for women in white-collar jobs and 50 for working-class women.

The plan to raise retirement ages is part of a series of resolutions adopted last week at a five-yearly top-level Communist party meeting, known as the Third Plenum.

6·7 days ago

6·7 days agohere are their demands from their letter calling for voluntary recognition:

- A horizontal staffing structure across the organization

- Two union-elected staff voting members to the Board of Directors

- Collective hiring and separation process, including collective decision making around layoffs, reduction of hours, new hires, and furloughs

- Full commitment to the Boycott, Divestment, Sanctions (BDS) movement and the Palestinian Campaign for the Academic and Cultural Boycott of Israel by December 2024

- Standardized pay progression and yearly Cost-Of-Living Adjustment raises

- Expanded health, commuter, paid leave benefits for all staff

- A Curatorial Committee made up of three union-elected members in addition to the Artistic & Executive Director and the Director of Programs to approve events

- Consolidated HR administered by a third party company

- Two union-elected staff representatives in both the Finance and Strategic Plan committees of the Board of Directors, ensuring budgetary allocations to Diversity, Equity, Accessibility, and Liberation work and the maintenance and upkeep of to the theater

will be interested to see how many of these they can win through collective bargaining

5·7 days ago

5·7 days agothe IWW successfully unionized three Peet’s stores previously, and hopefully this will be their fourth; they filed for a union election on July 8 and seem to be awaiting that.

5·7 days ago

5·7 days agoi’m pretty confident you are not correct that it’s too late; in any case, chill out a bit

don’t do this

2·10 days ago

2·10 days agothis is very belated but we will go back to doing these, we’re just in the middle of transferring our finances to a new host and that’s eaten up several months

21·10 days ago

21·10 days agoNOAA “should be dismantled and many of its functions eliminated, sent to other agencies, privatized, or placed under the control of states and territories,” Project 2025 reads. The proposals roughly amount to two main avenues of attack. First, it suggests that the NWS should eliminate its public-facing forecasts, focus on data gathering, and otherwise “fully commercialize its forecasting operations,” which the authors of the plan imply will improve, not limit, forecasts for all Americans. Then, NOAA’s scientific-research arm, which studies things such as Arctic-ice dynamics and how greenhouse gases behave (and which the document calls “the source of much of NOAA’s climate alarmism”), should be aggressively shrunk. “The preponderance of its climate-change research should be disbanded,” the document says. It further notes that scientific agencies such as NOAA are “vulnerable to obstructionism of an Administration’s aims,” so appointees should be screened to ensure that their views are “wholly in sync” with the president’s.

28·1 month ago

28·1 month agothis whole thing has been a mess so, here are some bullet points of what we expect going forward.

most immediately: both sides of this are going to have to make peace with being uncomfortable. it is Grail’s right to argue the premise that there is ableism against people with NPD; but, it is also the right of everyone else to disagree with that, and to disagree with it for personal experience reasons. if that’s a problem for you, don’t engage with this stuff and block people, full stop. genuinely: do something else. this is our third discussion on this subject and i have seen exactly zero minds changed as a result on either side, so i doubt you’re going to be the first if you’re obstinate enough.

if you would like more elaboration on the line we take here, please see our essay On Content Removal, and specifically this section:

However, from a pragmatic standpoint: Beehaw is ultimately a public space - curated as it may be - and you will be exposed to content you neither agree with nor feel comfortable with as a product of that. This is perfectly fine. It is also fine to disagree with some things we allow here that you personally would not. These are normal parts of existing in public spaces with other people and using services that are not your own respectively. But that also means you must be willing to compromise or take personal action to protect yourself sometimes - our moderation cannot and will not guarantee a completely agreeable space for you.

From a logistical standpoint: we simply cannot privilege your personal discomfort over anyone else’s, and we cannot always cater specifically to you and what you want. Your personal positions on right or wrong are not inherently more valid than someone else’s when weighing most questions of how we should moderate this space. There are often plenty of people who do not feel like you that we must also consider in moderation decisions.

secondarily:

- it is understandable that neopronouns (especially of the sort in play here) give people trouble, but if someone politely asks you to use their pronouns/corrects you on what their pronouns are then we’d request that you either do that or just disengage entirely. this seems pretty straightforward. you especially do not need to give your opinion on the validity of them, because it benefits nobody.

- same deal with the word “narcissist”–if someone doesn’t want to be called that personally, honor the request, find some other agreeable word to use between you, or just don’t argue and move on with your day. there are undoubtedly more important things you could be doing besides getting into an argument over whether this is a proper ask to honor.

4·1 month ago

4·1 month agowe’re obviously, contextually talking about deaths from heat, not from all the other stuff that happens on Hajj. don’t do this “you cannot be serious” routine when you simultaneously don’t even engage with the context of the question

19·1 month ago

19·1 month agoyes; as far as i’m aware there has never been a mass-death event like this in the contemporary history of the Hajj, although it’s always been arduous and more potentially deadly when it falls during the summer

9·2 months ago

9·2 months agoThe various initiatives — known as Tempo 30 in German-speaking countries, City 30 across Europe, Love30 by the WHO and 20’s Plenty in the UK and the US, the latter referring to miles per hour — have been gaining steam in recent years. Paris and Brussels introduced a default speed limit of 30 kilometers per hour in 2021, Lyons in 2022 and Bologna in early 2024, with Milan and Parma planning to follow suit this year. Beyond the EU, Wales introduced a 20 mph limit as the default for all residential roads in September 2023, and a couple of US cities, like Portland, have begun reducing their residential speed limit to 20 mph.

25·2 months ago

25·2 months agoyou may take the United Fruit Company’s name, but you can’t take its legacy of financing terrorism and violence in Latin America…

3·2 months ago

3·2 months agoMassachusetts has collected about $1.8 billion from a voter-approved surtax on the state’s highest earners through the first nine months of the fiscal year, the Department of Revenue said Monday in a quarterly report.

That’s more than $800 million more than what the Legislature and Gov. Maura Healey planned to spend in surtax revenue for all of fiscal year 2024, raising the possibility of a sizable pot that will land in an Education and Transportation Reserve Fund and the Education and Transportation Innovation and Capital Fund, both surtax-specific accounts, once the books close.

4·2 months ago

4·2 months agoALAMOSA — Over decades starting in 1985, the Colorado Mushroom Farm northeast of Alamosa sold millions of pounds of mushrooms grown and harvested within the building’s dimmed cavern to grocery stores in Colorado. Along the way it offered year-round employment to generations of immigrant workers, many of whom came here from Guatemala fleeing civil war and searching for a better economic future.

But when the farm filed for bankruptcy in December 2022, it owed thousands of dollars in unpaid wages to employees, some of whom had been subjected to unsafe working conditions and were injured on the job.

[…]Now, some of those workers are taking charge of their futures with the help of a powerful coalition of nonprofit and government supporters as well as Minsun Ji at the Rocky Mountain Employee Ownership Center, which works to dismantle economic systems that benefit a small few at the expense of many, especially working-class communities and communities of color.

It’s an American Dream in the making, but not without funding for an employee-owned mushroom co-op and the workers learning to navigate the hurdles of business ownership in a system that favors wealthy white entrepreneurs.

4·2 months ago

4·2 months agoalways fun after the wolf reintroduction vote from a few years back. here’s why they’re doing this:

Colorado is considered a prime habitat for wolverines, which are listed as a threatened species across the Lower 48 states by the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. Wolverines were nearly eliminated from much of the United States in the 1930s, experts said, but conservation efforts have helped the animal to make a bit of a comeback. In Colorado, the last confirmed sighting of a wolverine was in 2009, when one traveled down from the Grand Tetons.

Advocates for reintroduction said Colorado is home to the largest block of wolverine-ready habitat in the Lower 48, with about one-fifth of total suitable land. Wolverines are solitary animals that favor high-alpine environments.

7·2 months ago

7·2 months agoin this case: no, they’re just Filipino, and it seems to just be a contraction of Jupiter or something similarly banal. i think it would be prudent in the future to do a bit of double checking before we start accusing people of Nazis; you can easily check your assumption by just visiting their mastodon page, linked in the description of their kbin account.

Obviously, my point is that beehaw admins should accept that they made a mistake and refederate with sh.itjust.works. I would also recommend upgrading to the latest version of Lemmy, because it at least gives users the option of instance blocking. I understand that you intend to move to Sublinks or another platform in the future, but in the meantime you are neglecting your users by allowing the current implementation on Lemmy to languish.

unless we’re compelled to, it is exceedingly unlikely we will upgrade. we are fully committed to moving off the platform so it just makes no sense to prioritize Lemmy updates.

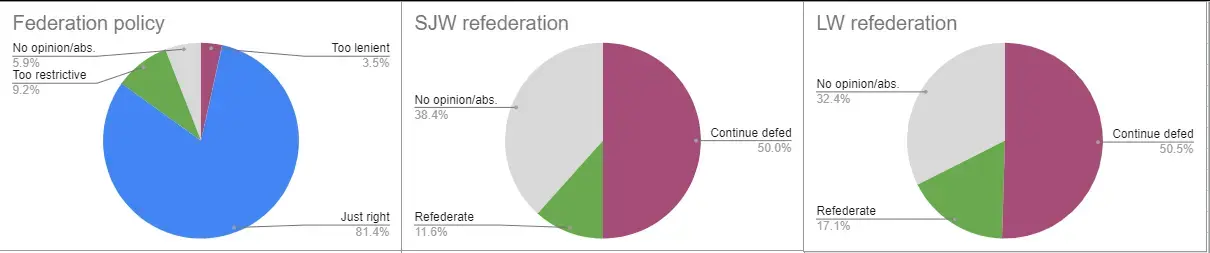

with respect to refederation: we already polled that with both SJW and LW months ago and were given a very definitive no, do not refederate from our userbase. only 11% and 17% of our users were in favor of refederation respectively, and majorities were fine with continued defederation from both. our defederation policy was also strongly supported. (i believe this is the first time these numbers have been posted because they were so definitively in favor of the status quo.)

At the time that they defederated SJW, Beehaw was more that 3 times larger, at about 12k total/3k monthly users. Now, SJW is more than 5 times larger than Beehaw, which has dwindled to just 450 monthly users.

we’re not and have never been in this for numbers so this is immaterial to us–we’ve been quite public that we’d be fine having a community of a few dozen people, because that’s what we were before the Reddit fiasco. in any case: please understand that we are not responsible for the health of the Lemmy ecosystem. and even if we were (which we reject categorically) we have definitively been told to leave the platform because of our disagreements with the Lemmy developers. bettering this platform is no longer a priority for us in any way–and it is the general opinion of the team that we wasted a lot of time prioritizing that given the developer antipathy toward us. you can read more on that here if you’d like.

13·3 months ago

13·3 months agothis is actually quite cute, i think.

Moderates

provided nothing else blocks it, this will once again go into effect starting in September.