TLDR you limey bastards built school roofs out of a material that was advertised as with a 30 year life span, and here we are 40 years later and its surprised pikachu faces all around.

advertised as with a 30 year life span,

It’s not clear to me from the article whether it was expected to only last 30 years at the time, or whether it was subsequently revised down in some way.

I mean, my guess is that many building materials may only guarantee some number of years, but it may be the norm for them to last longer. I assume that businesses selling stone do not rate, say, masonry for hundreds of years, though it clearly can last that long.

The article has:

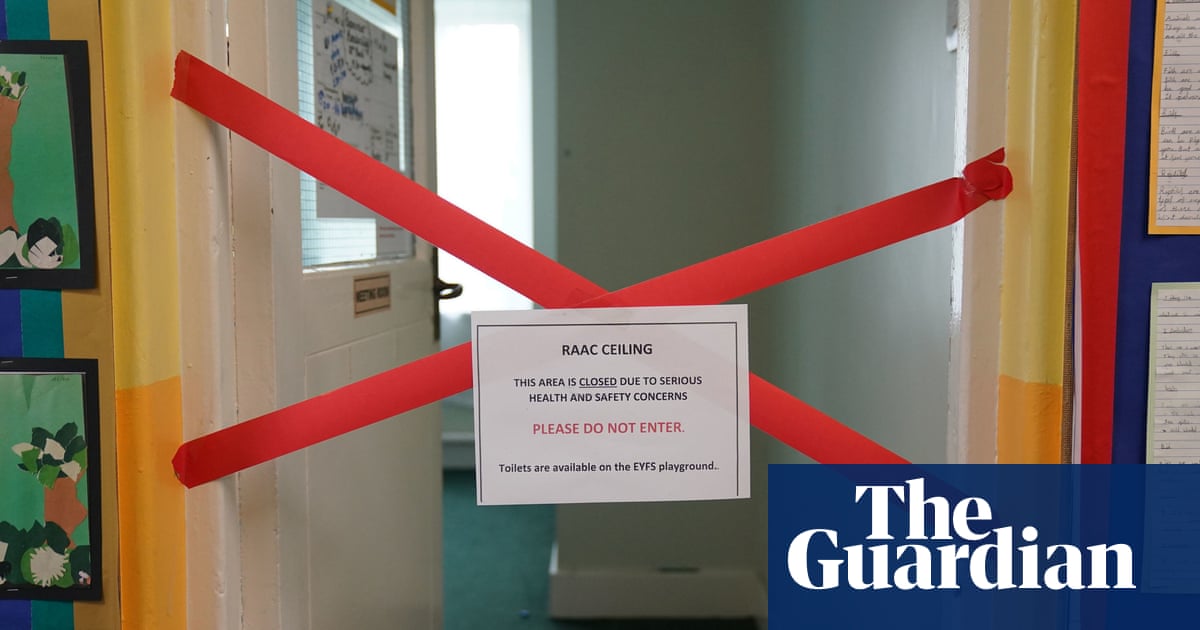

Raac, a lightweight building material, was commonly used in panel-form in public building construction from the 1950s to mid-1990s. It is estimated to have a lifespan of 30 years, and many structures have now passed that age.

EDIT: Yeah. From another article, it sounds like at the time it was built, it was not realized that the material would last only 30 years:

During the post-war building boom of the 1950s, 60s and 70s, reinforced aerated autoclaved concrete (RAAC) was something of a wonder material.

In the 1990s, when the material was still being used, structural engineers discovered that the strength of RAAC wasn’t standing the test of time.

The porous, sponge-like concrete - especially when used on roofs - could easily absorb moisture, weakening the material and also corroding steel reinforcement within.

As it weakened, it sagged, leading to water pooling on roofs, exacerbating the problem.

RAAC made in the 1950s was at risk of failure by the 1980s, the report concluded.

About 30 years ago, it became known that the lifespan of RAAC in many public buildings, including hospitals and schools was no greater than 30 years.

Some of the buildings constructed using RAAC were only intended to be temporary structures, regardless of the knowledge of the material’s true lifespan.

The Queen Elizabeth Hospital in Kings Lynn for example, was opened in 1980 and was intended to last only 25 years. But it is still being used today, 43 years later. It is finally being replaced, but only after it’s RAAC roof started to fail and had to be held up by hundreds of temporary supports.

Buildings like this would have been replaced long ago if consecutive governments had not failed to properly invest in our public infrastructure.

And timber frames are only manufacturer rated for 30 years. The Americans have been using them for decades, while in the uk we’ve only started to accept them recently.

You’re aware Europe has the oldest timber framed buildings and the us took their building lead from old Europe.

You act like Europe decided stone was the better solution when that’s just not true, Europe by in large deforested itself into leaving stone as the only affordable solution left and only then switched off timber framed homes.

Europe by in large deforested itself into leaving stone as the only affordable solution left and only then switched off timber framed homes.

The UK does import timber, though I imagine that greater distance adds cost.

https://www.eastcoastfencing.com/news/where-does-most-timber-in-the-uk-come-from

Says that Sweden is currently the largest single source.

Correct, they import timber now.

I’m surprised there’s not more academic papers about the effect of shipbuilding on global forests. Farming is probably a bigger factor but shipbuilding is responsible for a weirdly huge amount of old growth.

Source for 30 year rating? I’m not aware of such in either Europe or North America. I found a few sites reporting that number but couldn’t find an actual authority giving that rating.

Also, there’s a difference between a wood (or stick) frame and a timber frame, at least if you’re including North America in context. In our terminology, a timber frame has large timber beams and columns supporting the load, and dividing walls are put in between. A stick frame house uses smaller lumber studs, and most of the internal and external walls are supporting the floors or roof above.

American houses are stick frame, and with proper maintenance a stick frame house can last easily over 100 years. Wood doesn’t rot if treated and maintained properly. Settling of the foundation is a bigger problem, and simply subject to ground conditions which would impact even a steel frame house.

Timber frame is becoming more popular again for large buildings though, since ~12"/30cm timber columns have pretty good fire ratings, can support 3-4 stories, and are good carbon sinks for more environmentally friendly construction versus concrete or steel. My city is putting up some 3 story timber apartment buildings that look pretty awesome.

Long story short, wood is a great, renewable construction material if you’re smart about how you build with it and how you treat it.

30-45 years is what the frame manufacturers would give in guarantees, or expected life. Which is possibly why some mortgage providers class timber frame as non-standard construction.

In terms of actual age, the numbers I found suggest that properly maintained softwood frames can last in excess of 80 years.

Oh, bummer.

I do kind of wonder whether it would have been cheaper to, back then, go through and seal all of this stuff against moisture, if that is possible. It sounds like what kills it is exposure to moisture.

If they’re already starting to collapse and inspections are finding a lot of instances of degraded concrete, though, I assume that it’s too late for that.

EDIT: It also sounds like the stuff has been widely used in mainland Europe, not just the UK. I don’t know whether the UK being particularly rainy might be a factor, but if the UK is seeing serious problems now, then it might be worth taking a look at usage in mainland Europe as well.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Reinforced_autoclaved_aerated_concrete

RAAC was used in roof, floor and wall construction due to its lighter weight and lower cost compared to regular concrete,[1] and has good fire resistance properties; it does not require plastering to achieve good fire resistance and fire does not cause spalls.[2] RAAC was used predominantly in public-sector construction in Europe, in buildings constructed since the mid-1950s.[3][4] RAAC elements have also been used in Japan as walling units owing to their good behaviour in seismic conditions.[5]

Reading some other articles, it sounds like we in the US and the Canucks do have some as well, but not much, mostly because apparently wood is cheaply available and dominates as a material, and the American construction industry isn’t very familiar with use of AAC. There is only one small (13 person) US factory that produces the stuff, in Haines City, Florida.

https://www.resilientdesign.org/aac-an-ideal-material-for-resilient-buildings/

It’s no secret that autoclaved aerated concrete (AAC) has struggled to gain a foothold in North America. AAC is in widespread use in Europe, Mexico, and much of the world, but it has had trouble competing against wood-frame building here in the United States and Canada.

I couldn’t find reference to specifically the reinforced form (RAAC) in the US, but looking at the factory’s webpage, they list reinforced AAC roof panels as one variant that they can provide, so I assume that they must have sold some.

More like getting on for 60 years in some cases.

Fuck me I wish lemmy had awards

How the hell have we messed up concrete? The Romans had concrete that is still with us today.

The difference between a Victorian bridge and a modern one, is that the Victorian one was built to definitely stay up, while the modern one is built to just stand up.

Because just is all you need, when you can calculate so much of the design, and know the service life.

What’s happened here, is a lot of the buildings were built with a service life that was within the bounds of aerated concrete. The buildings were supposed to be replaced by now, but budget constraints have meant that they’ve been pushed beyond their service life.

Or in analogous terms: You have to stay in a house for a week, you buy some disposable plates and cutlery.

2 months later, you’re still there, and all the plastic forks have broken.Couple that with the bidding process for infrastructure contracts, and anything built in the last 40-50 years by government contract is likely to be falling apart before too long.

and know the service life.

According to other articles that I linked to in this thread, the problem was only discovered in the 1990s, that the stuff had a relatively short lifetime.

I’ve found nothing is more permanent than “temporary”.

It’s economically and environmentally bad to make things to be temporary and disposable. Stupid short term thinking.

This is true, but it’s also more expensive, which means the owners now don’t want to spend the extra 25% to make sure their building lasts 500 years instead of 50.

Roman concrete was more durable than most modern concrete, but was much, much weaker. It also relied on volcanic ash, which isn’t as readily available as the ingredients for portland cement. Being able to have larger freestanding spans and lower construction costs due to reinforcement is usually worth a much shorter design lifetime.

The reinforced aerated autoclaved concrete was clearly a mistake, trying to make a concrete foam to reduce weight meant that more water could get to the rebar and cause corrosion much more quickly than in normal reinforced concrete.

To be fair, the Romans also had a lot of concrete that is not with us today, there’s a bit of survivorship bias going on here.

Very true. But still, seams like we have been doing it long enough we should know what lasts.

We have definitely built concrete structures that have lasted a lot longer than 30 years. This was a very particular form of concrete construction that was apparently only a few decades old when the issues were discovered.

I mean, building one form of concrete structure doesn’t give us a complete understanding of every possible new variant invented and their tradeoffs.

Sure, but Roman concrete was also actually really good due to the ingredients used. They had self-healing concrete millennia before we came up with the idea.

A fair critique is the Romans built their shit to last and didn’t have advanced computers to calculate loads to just ~10% of failure, like we do now. We’ll use cheaper, local materials if it’s good enough. The Romans shipped ash and concrete ingredients halfway across Europe to make sure they were using the good stuff.

One thing to note regarding the self-healing concrete. They came across that formula by complete accident. All they knew was adding volcanic ash resulted in longer lasting concrete but wouldn’t have known about the lime clasts that would mix with water and refill cracks.

Anyone aware of the RAAC collapses the article refers to?

I’m sure there’s some nice big contracts going out to construction firms that just happen to donate to certain MP’s

Sounds like one was not identified and collapsed in 2017. Another was Singlewell Primary School in Kent in 2018.

When was RAAC flagged as a danger?

The lightweight concrete, which is a “porous” material, has long been recognised as having “limited durability”, according to the LGA. The Government has been aware of public sector buildings constructed with the material since 1994.

2017

The Standing Committee on Structural Safety was asked to investigate the suitability of the material after a school roof collapsed, although it is not clear which school this was.

2018

Another roof collapsed at a Singlewell Primary School in Kent. It happened above the school staff room, also damaging toilets, ICT equipment and an administration area. The collapse prompted Kent Council to write to other local authorities warning them to check for RAAC in their schools.

2019

A structural engineer investigating on behalf of SCOSS began to “frequently” encounter RAAC planks that weren’t fit for purpose and warned all those installed before 1980 should be replaced.

This is the best summary I could come up with:

The Labour MP Meg Hillier, who chairs the public accounts committee, said Raac was “the tip of the iceberg” of maintenance issues within the school estate.

She questioned why the situation had been “left to deteriorate for so long”, telling Times Radio: “In both schools and hospitals, there hasn’t been enough money going into buildings and equipment.”

Matthew Byatt, the head of the Institution of Structural Engineers, said any high-rise buildings with flat roofs constructed between the late 1960s and early 1990s could contain Raac.

The DfE’s U-turn – which means all buildings or areas with Raac must close – follows instances where the material collapsed despite it being considered low risk.

Speaking to BBC Radio 4’s Today programme on Friday, the schools minister, Nick Gibb, said the department had discovered a “number of instances” over the summer.

Sarah Skinner, the chief executive of Penrose Learning Trust, which has three affected schools, told the Today programme on Saturday that the notification on Thursday seemed “very late in the day”.

The original article contains 812 words, the summary contains 169 words. Saved 79%. I’m a bot and I’m open source!

The one I haven’t seen mentioned, but I would expect to be affeceted are universities. Lots of concrete blocks going up in the late 60s

Brutalism was also a thing in that period, and that had a lot of externally-visible concrete. But I don’t know if that specifically was linked to this particular RAAC stuff.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Brutalist_architecture

Brutalist architecture is an architectural style that emerged during the 1950s in the United Kingdom, among the reconstruction projects of the post-war era.[1][2][3] Brutalist buildings are characterised by minimalist constructions that showcase the bare building materials and structural elements over decorative design.[4][5] The style commonly makes use of exposed, unpainted concrete or brick, angular geometric shapes and a predominantly monochrome colour palette;[6][5] other materials, such as steel, timber, and glass, are also featured.[7]

In the United Kingdom, brutalism was featured in the design of utilitarian, low-cost social housing influenced by socialist principles and soon spread to other regions around the world.[4][5][14] Brutalist designs became most commonly used in the design of institutional buildings, such as universities, libraries, courts, and city halls. The popularity of the movement began to decline in the late 1970s, with some associating the style with urban decay and totalitarianism.[5]